Highlights

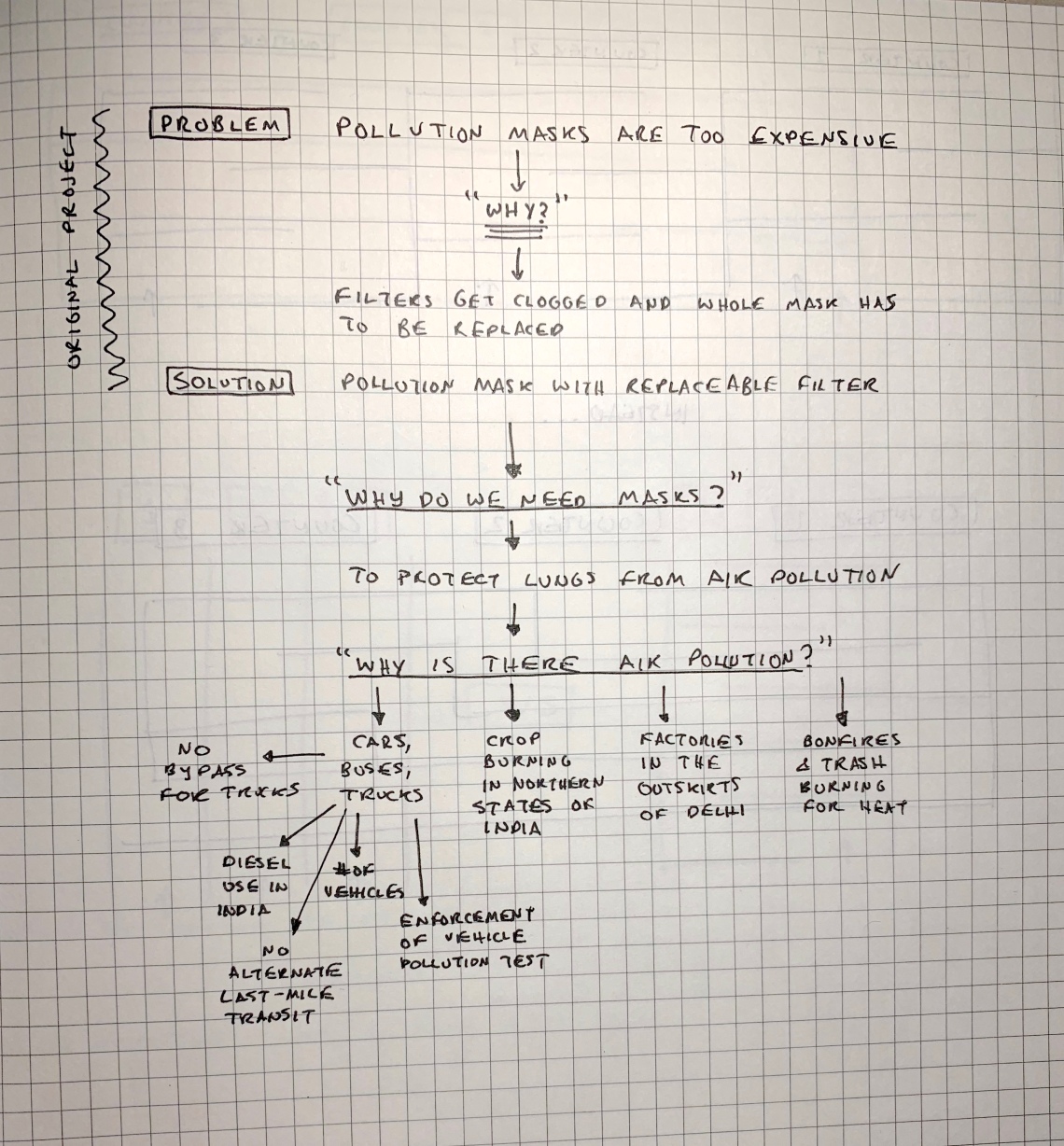

- Redesigned a pollution mask (here) to make it more affordable

- Traced the problem of pollution to its root cause: crop burning in Northern India

- Experimented with turning the hay that is traditionally burnt into cardboard and fabric. There were limitations with my manufacturing techniques; regardless, the cardboard and fabric showed some promise.

- Needed to understand the nuances of the problem, so I went to Punjab over winter break to do a deep dive into the root issue of crop burning.

- Talked to farmers, explored current initiatives, and immersed myself in the ecosystem.

- Learned a lot.

- Identified a few directions I could go down. I’m more informed, understand the issue in a lot more depth, and have identified some opportunities for social impact.

Here I go…

I’m in a cluster of farms near Nabha – a remote town in Punjab, India. My journey to get here began a while ago. Pollution is no stranger to any Indian; seasonal depression comes at another level as winter smog and pollution descend upon our northern cities for months at a time.

For the past few years, the situation has been getting considerably worse. When it comes to protecting oneself from pollution, one issue stood out to me: effective pollution masks are too expensive. As a problem solver, it was second nature to start researching and brainstorming solutions. My MVP? A pollution mask with replaceable filters that I outlined in a monthly problem-solving project in May.

That seemed to be the end of the story. I had half-assedly reached out to some suppliers and dome some preliminary 3D rendering, but it was the end of senior year, I was getting ready for college (and to escape from the pollution), and the project slowly fizzled away.

The beginning of college was a much-needed break from the pollution. My nose decongested, and I could breathe clearly for the first time in years. My skin improved. My eyes weren’t constantly irritable. You get the picture. Indeed, while most Los Angelenos complained about LA’s air quality, I reveled in what felt to me like paradise.

As September rolled around, however, Delhi’s pollution began to rise as it always does, and I saw glimpses of it in the News.

“New Delhi is once Again the Most Polluted City on Earth”

“Gurugram air worst in Country”

“City turns into a gas chamber again”

Calls with family only painted a more stirring picture as I saw the effects of pollution on their health and recalled my previous experiences.

In my previous post where I created a concept pollution mask, I discussed in detail the problems with mask affordability, so I’ll skip over going into that. Regardless, I wanted to return to the problem I had tried solving months before. This meant tracing the problem back. My pollution mask was merely a product for dealing with air pollution’s consequences on health. To make a true impact I was determined to re-approach the problem from its root:

After some more research, a key problem kept resurfacing: farmers in Punjab and Haryana.

The problem:

When Indian farmers grow crops like wheat, rice, and sugarcane, they are left with a straw byproduct which they burn at the end of their harvest. The practice essentially creates region-wide fires that emit harmful greenhouse gases and soot that blanket northern India for months. Imagine nearly 600 million tonnes (IIT Kanpur) of India’s surplus agricultural byproduct up in smoke.

An idea:

This is where I found myself taking a wrong turn. Although I had gone down a rabbit hole of research on the problem, I let myself be swept up by an idea: transform the straw into a product or industrial raw material that can incentivize farmers to sell their hay instead of burning it. It seemed like the perfect chance to empower farmers and also create environmental change.

Finding a bale of hay in LA was a challenge in and of itself. With a bit of luck, I eventually found myself with a bale of hay sitting in my college dorm room – and a grumpy roommate. Multiple Google searches, phone calls with factories, and YouTube tutorials later, I figured out what I might potentially be able to do with the material.

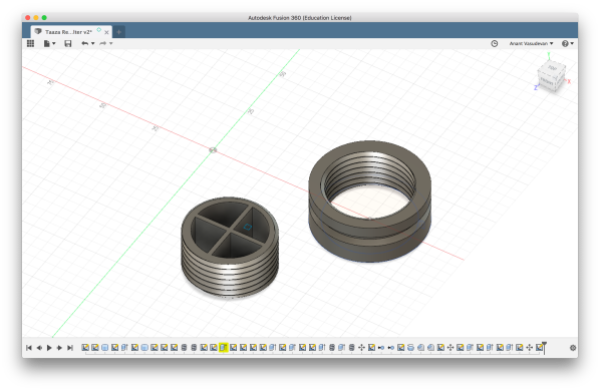

Ironically, I recircled back to the original problem as a materials proof of concept. I learned how to use Fusion 360 and just enough sewing to help me create this concept. Some quick branding and voila.

Again, this seemed great in theory, but I was isolated in a dorm room, 12,700 kilometers away from the actual problem.

It was time to go to the Gemba.

Research in the wheat fields of Punjab

Time for a disclaimer. This is where my story gets dense. I apologize in advance; I’m going to have an overflow of information that I tried my best to organize. It was hard because there were so many insights, stories, quantitative and qualitative research, and intricate ecosystems of problems and solutions. My mind is still reeling.

As soon as winter break rolled around, I found a way to get to Punjab. Punjab generates a substantial portion of the air pollution from crop-burning. Just in the state, nearly 19.7 mt of paddy straw is created annually, of which only 4.3 mt is utilized for non-burning related activities. So I got a place to stay in Nabha – a small town closest to the epicenter of burning, hopped on a train, and rented a moped when I arrived.

About 20-30 km outside of Nabha in remote villages, I began my research.

First glance problems with wheat burning (and why farmers do it):

- The window between harvesting the specific crops and sowing the next cycle is 10-15 days at most. This gives little time for using alternate methods of stubble removal.

- Combine harvesting machinery has proliferated across the region, but it leaves standing stubble and unevenly spread crop residue that farmers burn in order to clear the field for the next crop cycle.

- The byproducts of various types of crops have different values outside the field. Paddy, for example, has a high silica content and low calorific value compared to other crops, which limits its applications. Basmati Rice stubble, on the other hand, has nutrients which can be used as animal fodder.

- Farmers tend to think short term because they scrape by with the earnings from harvest to harvest. Change is risky; one blunder and they can fall into a vicious debt trap. This makes capital expenditure (for investments) and behavioral change harder to facilitate.

- Any solution has to get through the hurdle of politics and the rampant corruption in the region.

- Gaining the trust of farmers is a challenge. Farmers are used to being swindled by factories and loan sharks.

Some current uses for agriculture byproduct:

|

Use |

Pros |

Cons |

|

Burning |

Is fast and simple for farmers. |

Reduces soil-health. Causes severe air-pollution. |

|

Biochar: turn stubble byproduct into a soil amendment |

Biochar has fertilization properties which can improve crop yield for farmers and help them in the long-run. Famers need to buy less fertilizer and can even sell in the market for about 19rs/100grams. |

Factory-based solution using pyrolysis (any factory-based solution only caters to a small range of farms around it due to high transportation costs for farmers). Factories also typically only accept baled hay. The process still uses controlled burning. |

|

Animal Fodder |

Does not require baling. Pays for itself without the need to buy animal fodder. |

Can only be made out of certain crops. In the farms I visited, they only used Basmati rice as animal fodder – a common trend across the region. Heavy pesticide use can often make animals fall sick or animals will not eat it. |

|

Mulching |

Improves soil health – less need for expensive fertilizers. Machinery used is small-scale enough to be deployed at a farm level. |

Too many extra steps for farmers. The benefit is not visualized by farmers. |

|

Bio Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) |

Can improve energy independence of the region. Farmers can often breakeven in costs. |

A factory-based solution with the same issues. Baling issues (described in more detail later). Very little financial incentive and the same transportation costs for farmers. |

|

Briquetting: uses a machine to grind and compress waste into combustible material for fire |

Machinery used is small-scale enough to be deployed at a farm level. |

It still results in the burning of stubble. Machinery is a large capital investment. Cannot be sold to energy plants because it is banned by the Central Pollution Board of India. |

|

Pelletization: paddy pellets can be co-fired alongside coal in power plants. Can replace 5-10% of daily coal requirements. |

Machinery used is small-scale enough to be deployed at a farm level. |

Transportation costs -although cheaper- are still required for sending pellets to a coal plant. It still results in the burning of stubble. Machinery is a large capital investment. |

TLDR: Most of these solutions either rely on factories – an unscalable solution – or they require a process that is too tortuous and/or uneconomical for farmers.

The Happy Seeder initiative

The Happy Seeder initiative – piloted by the CII foundation – appeared to be a unique solution that was focused on behaviourally changing the way farmers grew wheat. The concept was based on new farming equipment called the Happy Seeder that, when used, can reduce the amount of stubble burning per farm. The foundation donated Happy Seeders to their 9 adopted villages, and I got in touch to learn more.

Currently, this is the process used by farmers during wheat harvesting:

- Use combine harvester machine

- Burn all stubble byproduct

- Apply “suhaga” (land leveler)

- Plow fields

- Sow seeds and fertilizer with the Rotavator

Interestingly, the government is promoting the use of mulching:

- Use combine harvester machine

- Run the mulching machine to chop and scatter the stubble

- Plow fields to incorporate mulch into the soil

- Apply “suhaga” (land leveler)

- Sow seeds and fertilizer with the Rotavator

This is a flawed strategy as it requires expensive mulching machines and additional steps with very little additional benefit. Without heavy subsidization, this will not fulfill its goal.

With the Happy Seeder, however:

- Use combine harvester machine

- Run Happy Seeder through fields with seeds (and reduced fertilizer requirement)

- Collect remaining stubble byproduct and burn it

The Happy Seeder essentially replaces the Rotavator and reduces the number of steps required. This lowers the fuel costs and time between crop cycles. It also reduces the amount of stubble that is burnt by up to 70%, and because the stubble isn’t burnt directly on the field, the soil retains its nutrients and less fertilizer/pesticide use is required.

The old process’s operational cost is about 3000 rupees per acre; whereas, the Happy Seeder’s is half that at 1500 rupees per acre (excluding the cost of equipment).

Problems with Happy Seeder

Nevertheless, even the Happy Seeder has its fair share of problems. After conducting surveys with farmers, I gleaned some key insights on the Happy Seeder rollout.

- Happy Seeder can only work with wheat when in reality many farmers grow multiple different types of plants. The Rotavator works with many more varieties of crops and makes more sense as an investment for farmers.

- The Happy Seeder cannot be run in the mornings when there is a lot of dew. An already small window is further restricted due to moisture.

- Even after the machines were donated free of cost, many farmers did not want to pay for the gas required to transport and run the Happy Seeder.

- Happy Seeder leaves some stubble on the field. This is actually good for the soil, but farmers perceive the field to be more unhealthy. Some farmers ended up collecting and burning all the leftover stubble, which defeated the purpose. If they had let it be, it falls down and within a few weeks, it decomposes and actually enriches the soil.

- Usage problems:

- Some farmers drove the Happy Seeder too fast; hence, the spacing of seeds was too far and they falsely blamed the Seeder for low output levels.

- The Happy Seeder’s angle of attachment to the tractor was incorrect in many cases because farmers try to use the blades like a plow. This is what they are traditionally used to with the Rotavator, and so they also falsely blame seeder when yield isn’t good.

- The Happy Seeder requires a 55hp tractor to pull it, and many tractors are not powerful enough. Getting a more expensive tractor would not be worth it just for a Happy Seeder.

A lot of overall behavioral, awareness and general product issues persisted. Since the Happy Seeder can only be used for wheat, it is a tough sell for farmers. Even then, it doesn’t completely eliminate stubble burning.

To truly create a comprehensive strategy for curbing stubble burning, a combination of solutions would be needed. Although the Happy Seeder trial initially showed promise; finding uses for the collected stubble is the only way to truly curb crop burning 100%.

Still, in order to collect and use the stubble, farmers need to bale the hay and transport it – each of which provides unique challenges.

Baling:

Without baling hay (or collecting it and using it for another purpose), some degree of burning will persist. But baling is expensive to do.

Baling hay is a low margin business and requires space and specialized equipment. A baler machine like the one below costs up to 150,000 rupees. In order to be able to bale the hay, it also requires spreading it out across the field, delaying the sowing of the next crop cycle.

Most farmers who actually get this done usually have a third party hay baler do the entire process for them (for about 1,500 rupees) and then sell it to the factory (for about 7 rupees per kg.). This excludes the additional transportation costs.

Essentially by the end of the process, farmers barely break even. Although baling has potential, the dynamic between the farmers and factories is the final straw – pun intended. The factories are thieves in the farmer’s eyes.

Most of the nearby factories in Nabha use financing schemes whereby they collect the baled hay and only pay back the farmers after 2 years (if at all). The value they assign to the baled hay is also based on its moisture content, a figure they arbitrarily make up to dupe the farmers.

One farmer I spoke to by the name of Darvesh mentioned how he decided to try baling the hay and selling it to the factory the previous crop rotation. He understood the consequences of crop burning and was intent on trying out a new solution – a progressive farmer on that front. He hired a baler and afforded 3 days to bale the hay, then he found a plot to store the bales and reduce their moisture content. Finding this storage space was a challenge he described in great detail; nevertheless, he let them sit under the sun for another 15 days. As luck would have it, the day before he was set to transport it to the factory, the sky grew dark and heavy rain followed. The factory ended up refusing to buy the hay because it was too wet.

Potential ideas/routes forward

I remind myself of my initial concept: Empower farmers by inciting demand (and thus market value) for the straw that is currently deemed a worthless byproduct.

Throughout this journey, hundreds of potential opportunities presented themselves. I boiled them down here:

Involving women in the value-add process for paddy:

One insight I had from my visit was the role of women in the farms. Many women were confined to household domestic chores. When farms are struggling to improve productivity, tackling female underemployment could provide multiple avenues for growth. Women could be involved in repurposing hay for example. Converting the straw into jute or even weaving it into handicrafts. Handicrafts, in particular, could market themselves using principles of ideo-pleasure/responsible consumerism – consumers could become a part of the solution.

Promoting long-term thinking amongst farmers:

Sparse records, the absence of expense tracking, and information asymmetry with loan providers highlighted a bigger picture of farmer’s finances. Without such systems, it can be difficult for farmers to gauge whether they are receiving a return on investments (especially when it comes to purchasing capital equipment), and subsequently, long-term thinking is hindered. Designing a simple finance tracking method could help farmers quantify investments, recognize long-term opportunities growth, and incentivize the purchase of capital equipment. Behavioral change can also be accelerated if causal relationships can be determined through financial tracking services.

Rethinking financing schemes:

The financial barrier for purchasing equipment can prevent farmers from engaging in better farming practices. If we turned to shared mobility, perhaps we could glean a practical solution. Society has been buzzing about shared mobility for cars, but farms are the perfect beneficiaries of such a service for farming equipment. Many of the tractor attachments (and tractors themselves) sit idle unless they are being used for a specific stage of the crop cycle. Their utility could be maximized if they were shared between farms who staggered their harvests by even a few days. There are already farming cooperatives that purchase shared equipment, but what if OEMs could offer a subscription service to farms that lower costs. What about a platform for individual farmers to subsidize the cost of their equipment by renting it out to neighboring farms?

Factory trust:

Factories have the potential to change the narrative on crop burning. Fixing their perception problem amongst farmers is therefore imperative. Even though the factories operate on very low margins, I wonder if the factories could be the ones who go from farm to farm (like a garbage truck) to pick up the hay from fields. This would distribute the workload so the burden doesn’t entirely fall to the farmers, factories could standardize the transportation network and reduce costs with scale, and factories could even potentially see an increased output (and increased trust with farmers). Additionally, although transport may be more expensive if the hay isn’t baled, I wonder if factories would be willing to simply accept piles of stubble, which farmers are able to collect faster and more easily.

Information tools:

Awareness and behavioral change both require effective information tools. The rollout of the Happy Seeder, for example, is suffering because there is not a comprehensive strategy in place to teach and promote new farming practices. There need to be more multi-media approaches and campaigns for shifting a farmer’s perception and promoting behavioral changes, only then can stubble burning be reduced on a wide-scale.

The Experience

As I find myself sitting in the Nabha train station with Tiger biscuits in one hand and chai in another, I think about my overall experience.

Part of it was just leaving the house with a backpack, hoping to figure everything out along the way. The language (Punjabi) was relatively new to me. The place was foreign. I only had my goal to guide me. Approaching this trip solo was a chance to channel street-smart thinking.

And it ended up being a lot of fun. On a moped I rented, I glided by sprawling fields of yellow mustard flowers on dirt roads with audiences of curious monkeys. It was customary for every farmer I visited to conjure chai out of what seemed like thin air, and I became borderline addicted to the stuff. At the village langars (the community-run service that provides free meals to anyone), I stuffed my mouth with spicy pakodas; in fact, the communities are so well knit that you can probably go months without having to make your own food. I climbed water tankers and soaked up the sun at the tallest point for acres. I hung out of trains with the scenery blurring past. This journey was a chance for me to revisit my home country with a fresh set of eyes, and I cherished the small details that I used to take for granted in this stunning place.

This was also an opportunity to get to know myself better. Spending time with myself in the evenings while eating street food offered a zen outlet of self-reflection to the journey.

Most importantly though, confronting social issues like this inspires me. It’s incredible journeys like these that give me purpose and drive, and as I recognize my goal in coming here, I realize this trip was just the beginning.

Hi there just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The text in your article seem to be running off the screen in Internet explorer. I’m not sure if this is a format issue or something to do with web browser compatibility but I figured I’d post to let you know. The style and design look great though! Hope you get the issue resolved soon. Cheers

Thanks for the heads up! I’ll look into this and hopefully get it fixed asap

Hi there! I could have sworn I’ve been to this site before but after checking through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Nonetheless, I’m definitely glad I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back often!

Hey Britney! Thanks for the support; I really appreciate it. I’ve been a little inactive recently, but new things are on the horizon that I’m pretty excited about. Stay tuned 🙂